The situation of hunting in Spain has changed as we could not imagine over the years. Not only in terms of the image that society has of it, which has changed a lot, but also in terms of legislation. To be more aware of this great difference, the Jara y Sedal team shows you what, in 1903, hunters were paid for the prey shot.

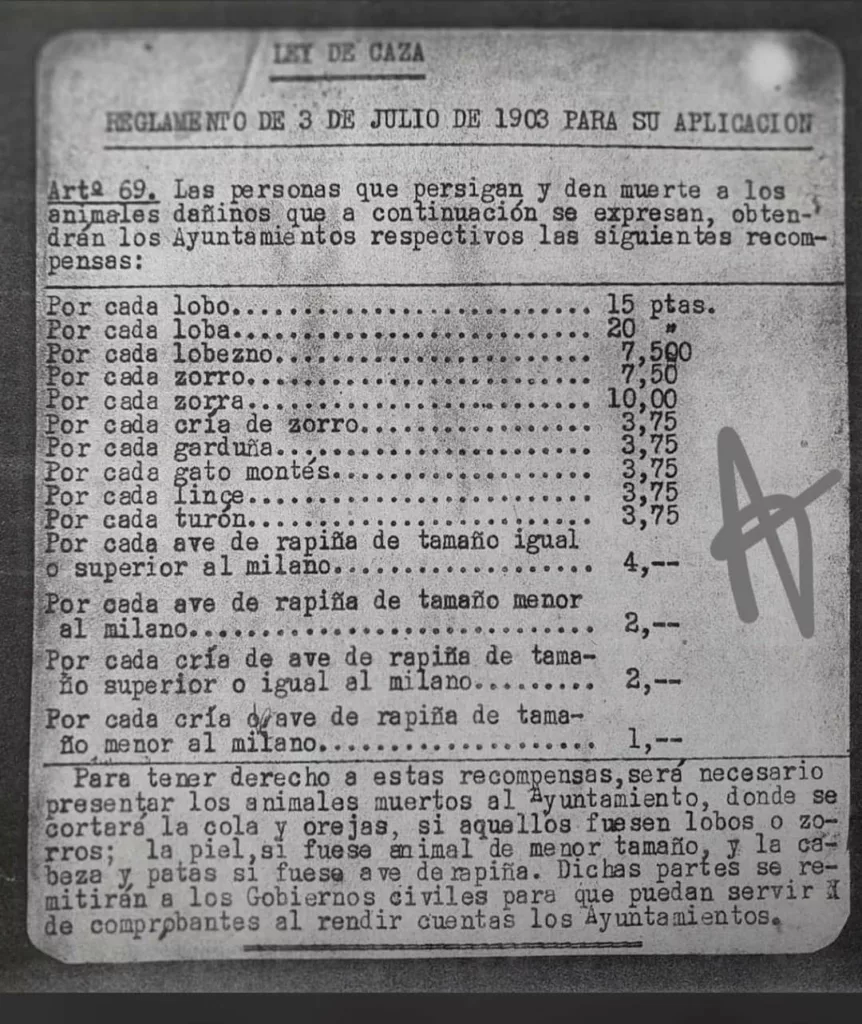

It is an image that the Regulation of July 3, 1903 for the application of the Hunting Law sets out. More specifically, what it reflects is Article 69, which established the rewards that were guaranteed for hunting certain species, such as the wolf, the fox, the so-called ‘birds of prey’ or the wild cat.

These were the rewards for hunters in the early 20th century

«The persons who pursue and kill the following harmful animals will obtain the following rewards from the respective City Councils», the regulation began.

In the case of the male wolf and the female, they established a value of 15 and 20 pesetas, respectively. If the hunters caught a wild cat, the amount was 3.75 pesetas; a figure that grew to four pesetas if it was a larger bird of prey.

Likewise, the reward for hunting a fox was 7.50 pesetas, and this rose to 10 pesetas for females.

From a reward for hunting wolves in 1903 to a ban in 2021

It has been 120 years since this was the case and the situation has changed so much that, today, the Spanish Government does not even allow hunting of the Iberian wolf. Despite the great threat that this species poses to, above all, agriculture and livestock, in 2021 it was included in the List of Wild Species under Special Protection Regime (LESPRE).

The circumstances of the wildcat are also completely different. Currently, the Red Book Assessment of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has warned that this species is in a situation of pre-extinction in the Iberian Peninsula.

Similarly, the Spanish government’s performance in this regard has also left much to be desired. Its recent animal law challenges the survival of this animal by prohibiting the control of stray dogs and feral cats. This will contribute, if it comes into force, to increasing the problem of hybridization, which, according to a Europe-wide study published in 2020, «may regionally threaten the genetic integrity of the European wildcat and even lead to the genetic extinction of local populations».

Finally, and returning to the 1903 text, it added a final nuance to establish who was eligible for these payments: «To be entitled to these rewards, it will be necessary to present the dead animals to the Town Hall, where the tail and ears will be cut off, if they were wolves or foxes; the skin, if they were smaller animals; and the head and legs if they were birds of prey. Said parts will be sent to the civil governments that can serve as vouchers when rendering accounts to the City Councils».